The lowest grade I earned in college was in an art appreciation class. Don’t laugh. It was an evening class; I was a working student. I loved the class, but one evening when the lights went out for the slideshow, my lights went out too. Three weeks later, I bombed the final because I apparently slept through a lecture on Cubism and was helpless on the essay I was supposed to write on Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. I’m still bitter.

As an adult, I’ve grown to love art and the museum experience. I worked at the Museum of Glass in graduate school. When my spouse I travel we always hit the local museum. I see art as a worthwhile distraction and museums as a sanctum--places to pause and to ponder.

Context matters. Recently, after getting strong recs from several friends, I went to the Tacoma Art Museum to see their 30 Americans Exhibit. In 2015, TAM (rightfully) caught holy hell from the black and progressive communities in Tacoma. TAM curated and hosted a reflection on the history of HIV/AIDS in the US that largely excluded the voices and the experiences of black Americans and artists. Like many social, economic, and health issues communities of color are disproportionately impacted by HIV/AIDS. Their exclusion drew loud, sustained, public (and IMO justified) protests.

There was “die-in” protest, charges the museum was "erasing black people," and several articles in local media outlets called out the museum’s curatorial practices. Christopher Paul Jordan, a local artist and one of my favorite minds in our community was blistering in his criticism. He told the News Tribune “AIDS has absolutely affected art history within black communities. This is beyond negligent. They’re not concerned with (black) stories. … This is not individual racism. It’s about a system within the museum that’s developed a white normativity. It’s a reflection not just of the museum but of Tacoma itself.”

This apparently provoked some introspection at TAM and one result of that introspection is the public programming around 30 Americans. 30 Americans is an exhibition of 30 black artists. To accompany it, TAM is hosting moderated panel discussions, a documentary film screening, a poetry slam, and several “free days” where people can experience the exhibit. The exhibit also has an interactive area where community members can leave their thoughts on pieces or review the feedback of others.

For this exhibit, TAM also reached out to the “old-guard civil rights community” (a conversation for a different day) and created an advisory committee to help with community promotion and engagement. This is a step in the right direction. When I worked at the Museum of Glass in the early aughts, I was often the only person of color--and rarely ever saw another black face--at museum events. A decade & change later, when I walk into the MoG and TAM, it feels much the same way. Though this exhibit suggests progress, it’s clear that TAM (and the Tacoma museum community writ-large) have a ways to go.

The exhibit itself. I am not an art critic and I’m not going to play one here. That said, here are some pieces that gave me pause or provoked an especially strong emotional response.

Duck, Duck, Noose is the centerpiece of the exhibition and the first thing you see when cresting the ramp from the main lobby. It’s a lot to take in... especially, when seen in juxtaposition to Glenn Ligon’s America, whose glowing presence on the north wall looms ominously over it.

I enjoyed both of these pieces, but appreciate even more what they are saying in concert. America’s racial history is complicated. My mother is from Arkansas; my father was from Mississippi. Their stories and why they left are in my bones. Most people, black and white, would rather not discuss it. But the historical influence of the Klan, particularly here in the Northwest is undeniable. Oregon was founded as a whites-only "racial utopia," the Klan marched through the streets of Bellingham well into the twentieth century, and don’t get me started on the white supremacist movement in Northern Idaho. This is our history. This is our inheritance. This is who we are.

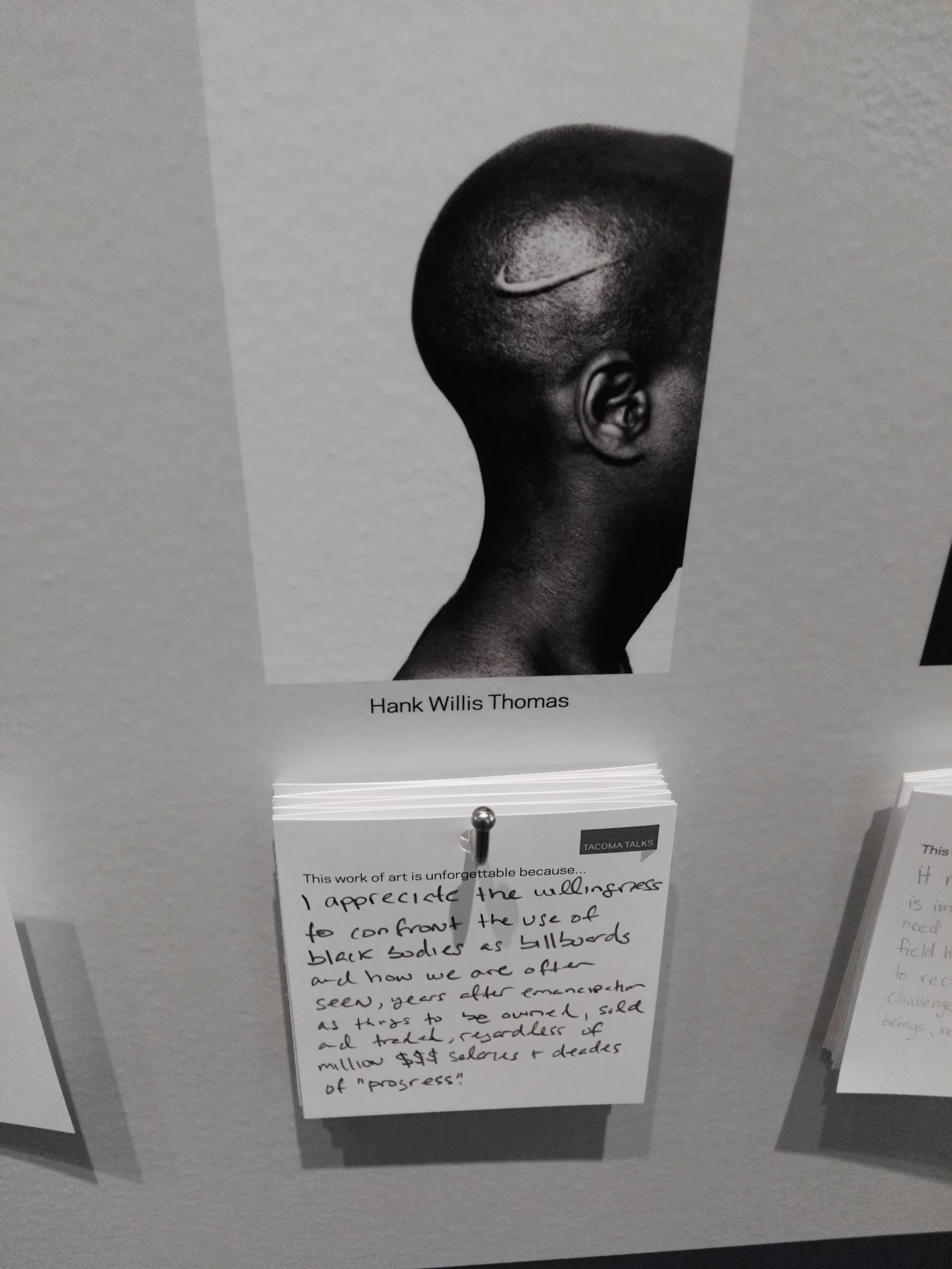

Branded Head speaks to my Olympia, anti-corporate, No Logos, twenty-five year-old self, and I think I would use it as my point of entry in introducing my students to the exhibit. Brand loyalty has always perplexed me, particularly the devotion to shoe companies among the non-athletic. Branded Head is muted and understated. But, it also stayed with me throughout my time in the gallery. This is the reproduction in the section in the gallery set aside for community engagement. You can see my scribbles.

Sleep. When I visited his exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum, earlier this year, Kehinde Wiley immediately became my favorite living painter. Period. His specialty is reframing classic and classically styled paintings by replacing the subjects with black youth. He works on a massive scale. Sleep measures 132” x 300.” Wiley’s work represents a pointed critique of our absence from the art world--the core of last year’s protests--I rarely see people who look me in museums, unless we're working. Wiley’s work is jarring in how bluntly he points out the marginalization of blackness, while simultaneously mocking the odd composition and poses of many classic portraits. Sleep isn’t my favorite Wiley piece, but I think it is very representative of his work and aesthetic.

I have my issues with 30 Americans and you likely will as well. But, that’s talk for tea or cocktails. Its public programming is TAM’s attempt to respond to critics and engage the community. I’m listening, not satisfied, but I'm listening.

Check out the exhibit now through January 15, 2017. If you’ve visited already, I welcome your thoughts and comments below.